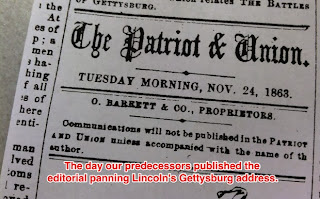

Something I missed recently, but I'll include it here in case you missed it too: coinciding with the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address on 19th November, a retraction of an 1863 newspaper editorial dismissing the speech as “silly remarks”.

“We pass over the silly remarks of the President. For the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall be no more repeated or thought of.” With these stinging words did the Patriot & Union of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania achieve infamy in the annals of journalism, by panning the presidential speech that lives as one of the most treasured orations in the English language.

Three weeks ago, the successor paper Patriot-News revisited this unkind judgement, suggesting that their predecessors were perhaps under the influence of partisanship, or of strong drink - whilst wittily observing that “the world will little note nor long remember” the paper's apology.

This is all good fun, but ahistorical, of which more below.

|

| Lincoln at Gettysburg (unknown date) |

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate - we can not consecrate - we can not hallow - this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us - that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion - that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain - that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom - and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Now to the question of how the Patriot & Union came to overlook history being made that day. It's worth reading “Living on the wrong side of history? The Harrisburg Patriot & Union's notorious 'review' of the Gettysburg Address” from Patriot-News website.

This deals with the issue historically, and discounts the playful suggestion that their 1863 predecessors were under the influence of strong drink. In the first place, the newspaper's own reporter described the President's speech in Gettysburg like this: "The President then arose and delivered the dedicatory address, which was brief and calculated to arouse deep feeling." But the crux is that the Patriot & Union supported the Democratic party, and was hostile to Lincoln, his conduct of the war, and his war aims. Moreover, the paper’s editors had been in put in jail for sedition a year before. So there was stuff going on.

As a final thought, I've often wondered if Lincoln really believed that the world would little note, nor long remember, what he said that day. He well knew he had crafted a masterpiece … surely he entertained the hope that the world would recognise this?

[1] This is the text most often reproduced. There are others, see Abraham Lincoln Online.