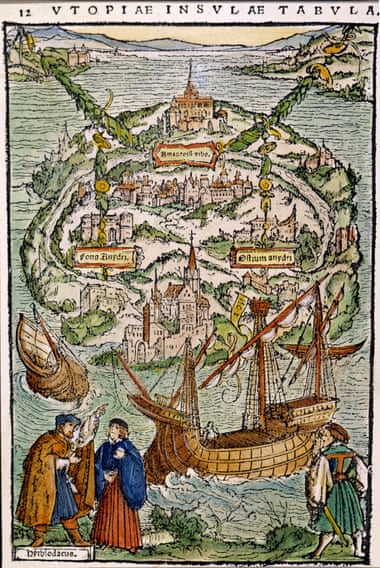

From Thomas More’s Utopia, 1516. This month is the quincentenary and Verso Books have brought out a commemorative edition. Must get this book. Sadly, came across it too late to drop any hints for Christmas.

|

| A woodcut by Ambrosius Holbein, illustrating a 1518 edition of Utopia |

They have built over all the country, farmhouses for husbandmen, which are well contrived, and are furnished with all things necessary for country labour. Inhabitants are sent by turns from the cities to dwell in them; no country family has fewer than forty men and women in it, besides two slaves. There is a master and a mistress set over every family; and over thirty families there is a magistrate.

Is utopianism any good?

There have been many utopias over the years, including visions of a socialist society. Utopian Socialism had many advocates in the early nineteenth century, like Charles Fourier and Robert Owen. Marx and Engels defined their own socialism as scientific socialism in opposition to utopian socialism. The difference being that Marx and Engels thought they had mapped out a route to get from here to there, whereas the utopian socialists merely hoped to persuade the capitalists to hand the stuff over. That’s my second-hand understanding of the distinction in any event.

Now two positive quotes about utopianism:

China Miéville in the Verso edition : Utopianism isn't hope, still less optimism: it is need, and it is desire

Eduardo Galeano, Uruguayan journalist, writer and novelist.1940-2015: Utopia is on the horizon. I move two steps closer; it moves two steps further away. I walk another ten steps and the horizon runs ten steps further away. As much as I may walk, I'll never reach it. So what's the point of utopia? The point is this: to keep walking.

477 years

The early voyages of European discovery, were, I imagine, amongst the influences that prompted More to write Utopia, and this has set my mind wandering off in another direction. Between Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the West Indies in 1492, and Apollo 11 landing on the Moon in 1969, is only 477 years. I find this a sobering thought.

|

| La Niña, 1492. Apollo 11, 1969

2009 replica of Columbus's ship La Niña. Apollo 11 landed the first humans on the Moon (Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin ) |