|

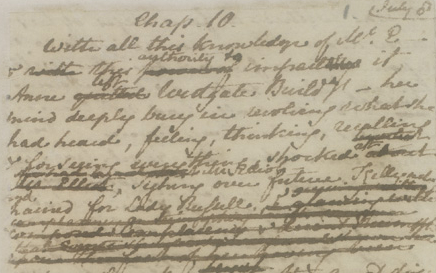

| Chapter 10 of Persuasion in the Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts Digital Edition curated by Prof Kathryn Sutherland |

But back to lunch, and Emma being the youngest of two daughters. Someone asserted that Austen was in error here, as you can be the younger of two but not the youngest of two. And indeed I've subsequently seen numerous posts on websites supporting this ruling.

The first thing to say about this point of view is that it assumes the existence of a Big Book Of English Grammar where such rules are written down. As I've lived 66 years without encountering such a book, I think I can plausibly suggest there isn't one.

I did however in the heat of debate make an ill-considered statement, which was that Jane Austen can't be wrong, and if she wrote the youngest of two then youngest of two is okay. Reflecting on this later I decided I ought to investigate whether Jane Austen actually took care of such matters; whether "youngest" is what she actually wrote; would she leave a decision about younger/youngest to the printer, and how carefully did she proof-read? I was travelling down a blind alley of course, because these questions matter not one jot. What's important is that the text of Emma is what it is, however many hands are responsible; not whether Jane Austen herself was interested in grammar.

William Gifford

Actually my blind alley was not entirely blind, for it led to me some new nuggets of knowledge. One of these is that Jane Austen did have an editor, William Gifford, who took great pains with grammar and punctuation. Indeed in 2010 a brouhaha erupted over a claim that his influence on the final text was such that Jane Austen’s style can't really be said to be her own. All this was attributed to Oxford Professor Kathryn Sutherland, though in fact the professor’s remarks seem to have been distorted. Be that as it may, we can be sure that the said Gifford wouldn't allow anything untoward to slip past him, and in the novel’s second sentence of all places.

|

| Prof Kathryn Sutherland and Jane Austen. The Kathryn Sutherland image is (so far as I know) a good likeness, whereas the Jane Austen one is not |

The Kathryn Sutherland controversy makes some fascinating reading, or fascinating to me at any rate, and I have a fellow Jane Austen society member to thank for drawing it to my attention. You could start with this blog by linguist professor Geoffrey K. Pullum. Writing in October 2010 when the spat over Austen's alleged failings in style and grammar was still fresh, he says he has seen no examples to back these claims up.

Dubious basis

Another nugget that came my way following my “Jane Austen can't be wrong” outburst: it seems that from about 1750 to about 1850 creating new rules of English grammar became a favourite passtime, and a prohibition on the “youngest of two” was being suggested around the time that Jane Austen was writing. There's plenty on this in the excellent grammarphobia blog which I've newly discovered. Here they reproduce the conclusion of Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage on the matter:-

“The rule requiring the comparative has a dubious basis in theory and no basis in practice, and it serves no useful communicative purpose. Because it does have a fair number of devoted adherents, however, you may well want to follow it in your most dignified or elevated writing.”

The blog authors Pat O’Conner & Stewart Kellerman were kind enough to email me with some additional comments on Jane Austen’s use of “youngest”, and they say that whilst there are differences of opinion here, it’s probable that Jane Austen was unaware of any “rule” banning a superlative with only two members; indeed many popular grammar prohibitions emerged only in the latter half of the 18th century and the early part of the 19th, so it’s not fair to call an author “incorrect” for ignoring a convention that was not yet firmly established in common usage at the time she was writing.

As I've already indicated, I'm reluctant to use the word “incorrect” at all, moreover I can adduce plenty of evidence against there being, even today, any firmly established convention that you can't be the youngest of two.

Finally, I nearly wrote "the authoritative" Merriam-Webster Dictionary of English Usage, but then I would stand accused of inconsistency, as I've already suggested that no-one is entitled to lay down rules. And that’s true, but Merriam-Webster is authoritative in this sense, that they have exhaustively investigated English usage, and if you want to know what’s been written and by whom, Merriam-Webster is a good place to look. Maybe all of this leaves you thinking that some of the things that interest me are very dull indeed, in which case I salute you for getting this far.